Comic strips have been called many things: drawn entertainment, drawn literature and even ‘little drawings'… but however you want to call them, there’s no doubt that drawing plays a vital room in comics. What lies behind the art of comics and what the roles of a cartoonist?

World Drawing Day, on 27th April 2023, is a unique opportunity to highlight the value of communication through drawing, a means of expression that has always been effective and versatile. This theme fits perfectly with the mission of IBSA Foundation, which since 2012 has been committed to promoting science in a way that’s accessible to everyone. Among its many related activities is "Let's Science!" a project to convey the importance of scientific knowledge to children, which once again shows the power of drawing as a universal means of communication.

The stars of this day are illustrators and their creativity and flair. There is a world to explore and discover, with many aspects still unknown to most people.

Set and costume designer: what does a cartoonist draw?

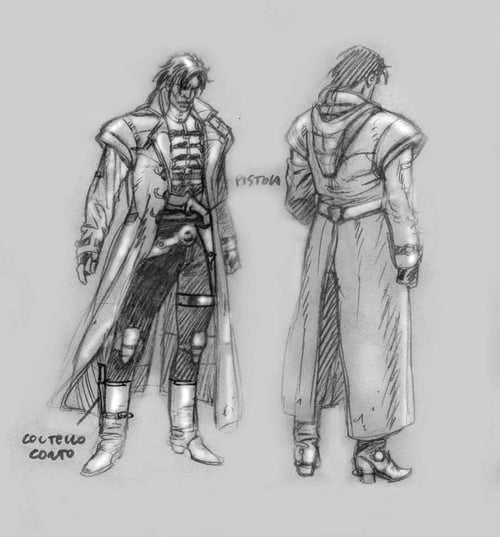

Character design ©Massimo Rotundo (Brendon Sergio Bonelli Editore)

Once they’ve received and read the script and understood the meaning of the story, the psychological make-up and the function of each character, the first thing a cartoonist does is to give a face and body to the characters, i.e. create an effective character design for each one.

Once this process is complete, they begin to make the character move. They verify that the iconic face they’ve created can change expression easily. The character has to laugh, cry or get angry, without changing their appearance, keeping the same facial features that make them recognisable. They also give strength and emotional depth to expressions. A character in a comic has to act, just like a real actor on the stage.

But that’s all not a cartoonist has to do with characters. They also have to be a costume designer. The character’s costume has to reflect their personality. Clothing is linked to the character’s ‘social group’. Jackets and ties, etc. reflect serious professional (lawyers, accountants or estate agents), while studded leather and piercings will suggest young punks…and so on, with everything in between.

As we’re already beginning to see, being a cartoonist is a ‘job’ that encapsulates many others. As well as being a costume designer, a cartoonist is also a set designer, as they set the scene. Just like in film or theatre, an illustrator has to graphically create the spaces where actions will take place. This has the same logic as the ‘costumes’. Locations must create the atmosphere of the story.

From the experience of Let's Science, we can clearly see how children often get carried away by the fantastic adventures of their heroes without realising how much science is part of the plot. By harnessing the power of comics, we can transmit the importance of scientific knowledge to young people, so they discover how the laws of physics, biology and chemistry underpin the exploits of their favourite characters. Once again, drawing proves a universal means of communication that can involve and excite children about science in a fun and captivating way.

The layout: the cartoonist becomes a director

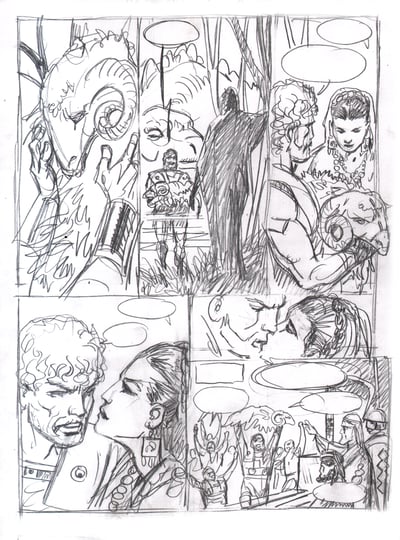

Layout © Massimo Rotundo

In the layout, a cartoonist creates each individual frame, taking care to maintain the balance of the whole comic strip. They’ve received detailed instructions from the scriptwriter. But don’t be fooled... here a cartoonist is not just someone who follows instructions.

Framing can vary by distance and camera angle and these variations usually depend on the taste and sensitivity of the cartoonist, as well as on the style and genre of the story. As well as having a technical function purpose, framing also has its own precise narrative, psychological and emotional meaning. And frames can’t be used interchangeably simply according to aesthetic taste, but have to be chosen on the basis of their meaning. So cartoonists always need to be clear about the meaning of the story and never force it to bend it to their own aesthetic and artistic needs. The illustration has to work for the story, and never the other way around!

Pencil drawing: free expression

This is the stage in creating a comic strip when the cartoonist starts to enjoy complete freedom of expression. When creating and defining characters and layout, a cartoonist shares the burdens (and rewards) with the scriptwriter, as well as following editorial guidelines, but when they pick up their pencil, they become purely an illustrator. They can now give full reign to their technical skills because a real professional must understand and perfect the rules of anatomy, perspective and life drawing. In fact, no one needs such a vast professional background as a cartoonist. They need to bring to life whatever a scriptwriter has come up with. For example, drawing the character Tex jumping out of a first-floor window, landing on a horse and galloping off, means knowing how to draw a moving body, the relative perspective, and the anatomy of the horse, both while standing and galloping. No obstacle can stand between what’s asked of a cartoonist and what they put on the page.

The biggest difficulty a cartoonist faces is having to reproduce reality through graphic symbols. They can do this in various ways. Some have an almost photographic, hyperrealist style. Some use a complex style made up of lots of dashes and symbols. Others stylise as much as possible, even taking the iconic language of comics to the extreme. But however it’s achieved, every cartoon has to be believable and lifelike. It doesn’t matter whether a gun looks real, but we have to believe that it can shoot and that its bullets can kill. This is why a cartoonist always starts from real life.

Inking

Technically, this phase involves going over the pencil drawing with ink. This is why it’s called ‘inking’ in jargon, because of the ‘ink’. But some professionals use other tools: anything from felt tip pens to biros, from nibs to brushes and special software. There’s no one rule. The choice depends solely on the cartoonist’s sensibility and taste. From a technical point of view, inking makes the drawing more evident and highlights its details by using shadows and so-called ‘blacks’. This contrasts with the white in the drawing so that the important parts stand out even more.

However, inking is not just a technical step, it also gives a style to the drawing. Because, in the end, a cartoonist is an artist who uses artisan methods therefore, like all artists, their graphic style always makes them unique and distinctive.

The world of comics is a world full of secrets and immense communication potential. With their immediate ability to impart information in a simple and accessible way, cartoonists have an important role to play in conveying knowledge. So let’s celebrate cartoonists on World Drawing Day, with an awareness of how important they are in promoting art and science.